The Boston Museum of Fine Arts is offering a rare opportunity to see some of the essential aspects of modern painting laid bare, as if under the intense illumination of an educational

anatomical theater.

In two concurrent exhibitions, adjoining rooms link a survey of the late Boston painter Hyman Bloom's work with a gallery containing one of Jackson Pollock's most important paintings along with a contemporary painter's answer to it.

|

| Katharina Grosse, Untitled, 2017, with Jackson Pollock's Mural in the background. |

Bloom painted to great acclaim in his day but when the New York abstract expressionist scene he helped to inspire took off, he stubbornly dug his heels into Boston and stuck to representation, and therefore has largely been neglected until now. Pollock painted his breakthrough 1943

Mural for a hallway in Peggy Guggenheim's Manhattan townhouse when he was still relatively unknown and it launched his career.

|

|

| Jackson Pollock, Mural, 1943 |

At 48 feet wide by 16 feet high, Katharina Grosse's room-sized kaleidoscopic response to Pollock's

Mural says a lot about the distance between contemporary practice and the mid-20th-century Pollock that inspired it. A freestanding painting hanging from floor to ceiling in the middle of the gallery, Grosse's

Untitled is meant to be walked around and "enjoyed in the round," as the wall text says. The text notes that it fits into her recent body of free-hanging works which "investigate painting's potential to live off the wall, to respond to and confront the world." As

this insightful reviewer says in passing while writing about Hyman Bloom's work, it "extends the post-easel scale championed by Clement Greenberg," the critic who

really launched Pollock's career (as Greeberg put words around the nascent abstract expressionist movement at the time).

But it doesn't "confront" the world so much as get a little in the way of it, occupying as it does a very substantial space between painting and sculpture. But that's part of the point, and it is delightful to be immersed in (if not quite "confronted" with) so much luminous color (light shines through the canvas, illuminating it from both sides). She's updated Pollock's colors but is working with basically the same palette of dripped and blurring pinks, whites, yellows and greens.

|

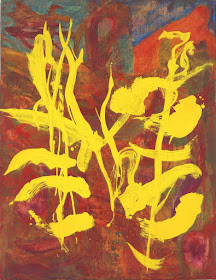

| DETAIL: Katharina Grosse, Untitled, 2017 |

In style and conception, Grosse's work combines the sensibility of abstract expressionism with the saturated colors of Pop and the materials (spray-paint and stencils) of contemporary street art. The result is a visual symphony of intricate yet exuberant painterly gestures and ravishing passages of eye-popping color. Surely the curators had something like this in mind when in an inspired move they placed one of Hyman Bloom's equally colorful canvases at the juncture between the two exhibitions.

Along with Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Pollock greatly admired Bloom, tagging him as "the first abstract expressionist," a moniker he rejected. There's so much to say about Bloom's incredibly vital paintings. However, I wouldn't have to say anything if they were treated as they should be: hanging in the world's most prestigious museums alongside peers Goya, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, and above all Rembrandt and Chaim Soutine.

I can't get my arms around the this exhibition far enough to document it here. Just go see it (if you are willing and capable of seeing paintings of corpses and flayed bodies as beautiful). Bloom's unforgettable and unflinching paintings are visceral and visionary, philosophical and spiritual, grotesque and beautiful, as difficult to look at as they are to look away from once their scintillating skeins of color have charmed your eyes.

|

| Hyman Bloom, Rocks and Autumn Leaves, 1949-51 |

|

| DETAIL: Hyman Bloom, Rocks and Autumn Leaves, 1949-51 |

|

| Looking back from the Hyma Bloom toward Grosse's Untitled - photographing it for interesting color effects is absolutely the appropriate response to this work. |

|

Hyman Bloom, Autopsy, 1953

|

|

| DETAIL: Hyman Bloom, Autopsy, 1953 |

Bloom proves the lie to the notion that scientific dissection destroys beauty. His subjects may be flayed bodies and cadavers undergoing autopsy, but his paintings are really about the redemption and transformation of flesh and gross matter into transcendent spiritual fire. Bloom smashes open the human body to reveal that its veins and organs are glowing wings and feathery flows ablaze and humming with mystical significance.

|

| Hyman Bloom, Self-Portrait, 1948 |

|

| DETAIL: Hyman Bloom, Self-Portrait, 1948 |

|

| Hyman Bloom, The Anatomist, 1953 |

|

| DETAIL: Hyman Bloom, The Anatomist, 1953 |

Woe to the painter who gets sandwiched between Pollock and Hyman Bloom!

I'm afraid that, between

Bloom's life-and-death pyrotechnics and Pollock's writhing archetypal abstractions, Katharina Grosse's otherwise sparkling and enjoyable painting comes up short. The Pollock alone shreds it.

Why? Because when you stand and look at the Pollok you don’t just see colors and shapes. If you study it and listen, allowing it to say what it has to tell you, you will begin to free associate and see into your own subjective experiences, into memories and archetypes, hints of mysteries, beauties, and horrors

. You will absolutely see a procession (the dark, rhythmical vertical lines), suggesting

a ritual pagan dance and/or a mournful human cortege, and you will realize it's a radical take on one of the most ancient forms of visual art, the frieze (figures arranged in a horizontal strip, as along the sides of the Parthenon). You see parts of animals, you see heads, torsos, bodies, and when you step back you see raw primitive forces liberated from any body

, all rendered with constant tension between elegance and excess, the raw and the refined.

You see movement, force, primal life concentrated, distilled

and set in motion - because in the colors and the forms there is clearly pink flesh, splattered blood, tearing matter, bone, and animating spirit. It is a different proposition entirely from Grosse's colorful, even cheerful sprays and drips. There you will see nothing of the sort.

But I suppose one might accuse the Pollock in this reading of being "overdetermined," burdened with an excess of drama, and that's fine. But why does the answer to such have to be frivolity? Why bright shiny things that catch the

eye, beauty without any angst - as if angst itself were passe

. As if our world were any more stable than it was in 1943.

So is it old fashioned now, as the Grosse implies, to seek meaning in art beyond intellectual games? Is it old fashioned to want art to impinge on the human condition? Shouldn't we all just be content with the jolt of novelty, the play of ideas, the seduction of an exquisite entertainment? I don’t think so. I think if Grosse was a grittier thinker, maybe it could’ve been a more meaningful dialogue.

Whereas Bloom was interested in what's beneath the surface, Grosse's work is appropriately titled Untitled, because ultimately (compared to the Pollocks and Blooms) it's a painting of nothing. That is, its surface is its content, in that it's largely about painting-as-colors-sprayed-onto-the-air. To paraphrase, Grosse herself sees the work as very like her "murals" (think artistically spray-painted buildings) lifted off their structures and inserted into space. It's not that Grosse isn't a brilliant colorist, a maddeningly fine painter and a daring conceptualist to boot. It's that putting her next to giants like Pollock and Hyman Bloom and lauding her, as the wall text does, as "one of her generation's most important artists" (she was born in 1961, btw) really just underlines the lack of gutsy, substantive painting on the contemporary scene today.

And that is why Bloom was a visionary and Jackson Pollck's "Mural" will last as long as civilization manages to carry on while Katherina Grosse's beautiful

Untitled will be forgotten.

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts is offering a rare opportunity to see some of the essential aspects of modern painting laid bare, as if under the intense illumination of an educational anatomical theater.

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts is offering a rare opportunity to see some of the essential aspects of modern painting laid bare, as if under the intense illumination of an educational anatomical theater.